- Home

- Deno Trakas

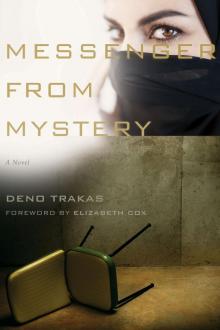

Messenger from Mystery

Messenger from Mystery Read online

MESSENGER FROM MYSTERY

Pat Conroy, Founding Editor at Large

MESSENGER

FROM

MYSTERY A Novel

DENO TRAKAS

FOREWORD BY ELIZABETH COX

© 2017 Deno Trakas

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.sc.edu/uscpress

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/

ISBN 978-1-61117-733-6 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-61117-734-3 (ebook)

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Front cover photographs: top: © visualspace/istockphoto.com; bottom: © Ryan Klos/istockphoto.com

FOR KJ, CC, AND FB

The way of love is not

a subtle argument.

The door there

is devastation.

Birds make great sky-circles

of their freedom.

How do they learn that?

They fall, and falling

they’re given wings.

Rumi, 13th century Persian poet and Sufi mystic,

from The Book of Love, translation by Coleman Barks

FOREWORD

After years of reading short stories and poems by Deno Trakas, I am already an admirer of what wonders he can achieve with language, images, and characters. Now, in his first novel, Trakas shows a talent for enlarging his focus and sustaining the keen interest of his readers in a richly honed cast of characters and a complex narrative unfolding against an historical event: the capture of Americans as Iranian hostages in 1979. A clash of cultures, the pull and push of personal relationships, and rising senses of duty and forgiveness create the driving force of this novel, but at its beautiful beating heart, this is a profound love story.

The novel focuses on the cloistered world of Jay, a University of South Carolina graduate student in English. He teaches his students literature and focuses on his comprehensive exams for his PhD, but this young man has never been required to risk or commit to a cause greater than himself—until he develops a strong connection with Azi, a student from Iran. Her beauty, intelligence, courage, and worldview all beckon Jay. At first, he lives with a kind of loose faithfulness to her, without real loyalty, but his commitment grows, as does the distance between them, when Azi returns to Iran. In Trakas’s capable hands, we come to know the deepness of the bond between these two students of very different worlds.

As global dangers escalate and Azi’s life becomes threatened, decision and action are demanded of Jay, and his innocence in the world at large begins to unravel. William James calls this kind of unmasking “a tolerance of facts in opposition with each other. The truth is too great for any one actual mind, many minds are needed to encompass an understanding of life.”

During the Carter administration, when American hostages are captured by the Iranians, Jay’s world becomes overshadowed by a wider world of terrorists, foreign countries, political maneuvering, and vast cultural differences he has never imagined. His high-minded literary ideals and any notions of heroism he might have entertained all fail him as he becomes caught in the dangers of an Iranian conflict. Trakas describes these events with compelling peril and threat. He makes the heart jump with the risks of capture or death, and we wonder if, after such harrowing experiences, this quiet student and teacher can ever return to his former life within the insular sanctuary of the academy. Jay’s perceptions, which had been so carefully settled (and ensconced in poems and literature), are shattered and his view of the world and of himself are inevitably altered.

Jay becomes entangled in the politics of terrorism and his actions awaken both him and the reader to a world of brutality and callousness. The hostages captured in the political conflict between nations become a mirror of the kind of hostage-taking we do to each other, and to ourselves, as we separate ourselves from seeing or understanding those of other cultures. And the questions come to mind: When we begin to understand another person’s suffering, what then is our responsibility? How much should we risk for others? For someone we love?

Rumi says, “Love is the way messengers from the Mystery tell us things” (as translated by my brother Coleman Barks), and love has much to tell to Jay and Azi. When this cloistered young scholar awakens to the ruthlessness and threats of the world, as well as to his deep love for Azi, the momentum of the novel makes the reader mindful of a variety of hostages—political and personal. Through lovers and terrorists, Trakas unmasks this very human trait of our selfish blindness to the plights of others. He explores the courage it takes to amend this trait in ourselves through empathy and action, and to move at last, with heretofore unknown strength, against our own self-interest and out of a love that is greater than ourselves.

ELIZABETH COX

PREFACE

Every writer of historical fiction sets his or her own parameters for the interplay of the factual and the fictional. When I read a historical novel, I want to know what those parameters are, and I’m frustrated if they aren’t offered, so I’m going to tell you what they are in my book: the background and events of the Iranian Hostage Crisis of 1979–1981 are true. I’ve researched them and related them as accurately as I can, drawing from excellent nonfiction accounts such as All Fall Down: America’s Tragic Encounter with Iran, by Gary Sick, the White House Aide to Iran; Crisis: The Last Year of the Carter Presidency, by Hamilton Jordan, President Carter’s Chief of Staff; Guests of the Ayatollah: The Iran Hostage Crisis, by Mark Bowden, an award-winning reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer; Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President, by Jimmy Carter; The Man in the Mirror: A True Story of Love, Revolution and Treachery in Iran, by Carole Jerome, Canadian journalist and girlfriend of Sadegh Ghotbzadeh; Witness: From the Shah to the Secret Arms Deal, An Insider’s Account of U. S. Involvement in Iran, by Mansur Rafizadeh, former chief of SAVAK; and a half dozen other books. However, the rest of my story is fiction.

Hamilton Jordan, Carter’s Chief of Staff, and Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, Iran’s Foreign Minister, play important roles in the story but do not have speaking parts in my novel. My other characters are not based on real people, except that Richard has the sense of humor of my friend Steve, Dr. Sheldon has some of the admirable qualities of Professor Don Greiner, and Oman Lare gets his name and spirit in an odd way from my friends John Lane and Scott Gould. However, if you recognize yourself in any of the characters and like the portrayal, then of course I was thinking of you.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

During the, oh, thirty years that I’ve been writing this book—I’m a slow learner—I’ve asked many friends and family members to read parts of it and give me feedback. Rather than try to list them all and invariably leave some out, I’ll just say you know who you are, I thank you for your encouragement and helpful comments, and I’m sorry for not naming you here. But three people—Kathy, Steve, and Jonathan—have read the whole manuscript more than once, more than twice, and their faith and good advice have sustained me and made the book much better than it would’ve been without them.

PROLOGUE

The Iran hostage crisis: it’s been thirty-five years, but I remember it vividly, especially my ignorance before it happened. We didn’t have CNN back then, and most of us didn’t have PCs. No Wikipedia or Google. We didn’t know what Islam was, what an Ayatollah was—we didn’t even know many of the countries in the Midd

le East. And of course we didn’t know that one day Muslim men would fly planes into our tallest buildings.

I’ve been unable to write this book about my small part in the crisis, even though my best friend Richard, my advisor in all things literary, has encouraged me to do it ever since I returned from Iran. But now I have to do it for Azi, for Oman, for Garrison, for all those who can’t. And for myself too, to put us all together once again, to be the memory-holder and the meaning-maker. I have to write it because, as the novelist Lois Lowry said, the worst thing about holding memories isn’t the pain, it’s the loneliness—that’s why they have to be shared.

PART I

CHAPTER 1

AUGUST 1980

When Azi stepped out of the plane into the glaring light of a late summer morning in Athens, she looked like a black and white photo from my past. She wore a plain black dress, little makeup that I could see, no red lipstick, and her honey skin was pale, as if diluted with milk. Then I saw the glint of one of the garnet earrings I’d sent her. But black and white, red, whatever, it didn’t matter, it was Azi.

As she walked across the tarmac, she glanced around as if she were looking for me or looking for danger, or both. I held up my sweaty hand, pressed it against the glass, but she didn’t see me inside the terminal as she disappeared into the building and the customs lines. A half hour later, in the travel-weary, multi-national crowd of strangers at the baggage claim, there she was again, there I was, in a foreign place, somewhere I had never traveled, both of us thrilled and amazed that we were anywhere together again after eight months, and without speaking we melted into a hug, one of those rare, full-contact hugs that’s both soft and firm, sexy and soulful—her body, thinner than Nadia’s, fit mine just so—and I wondered if there was any force in the universe that could make me let go. She trembled in my arms and began to cry. Her tears triggered flashbacks of our first awkward date, and all the simmering love bubbled and popped in my chest.

Finally I found my voice and said, “Are you okay?”

She pulled away, looked at me as if to double-check, smiled, flicked her wet cheeks with her fingers. She put her hands on my forearms as if for balance. “Yes, Jay, I am sorry. Why I cry? I am happy for to see you. Is long time. Is hard to believe.”

“Yes, very hard to believe. You look great.”

Baizan had asked if I wanted him to come to the airport, and I was glad that even though I’d never done anything like this, and I was nervous and scared, I’d said no—I needed time alone with Azi to let our emotions run, to see where they might lead us, in this time and place, with what I had to ask of her. I’d planned for us to talk over drinks at the airport—she had no idea what this was all about—but the airport was chaotic, noisy, and stuffy, so I said, “Let’s get your luggage and get out of here.”

The taxi was not air-conditioned, so between the dusty heat rushing in the windows and the bouzouki music blaring from the radio, conversation was nearly impossible. I tried to make small talk—How was your flight? How have you been?—but it wasn’t the time or place for big talk, so I gave up. We sat back, stuck to the seats, holding hands awkwardly, exchanging smiles awkwardly, not enjoying the long ride and unimpressive neighborhoods that spread like rubble between the airport and the city until all of a sudden, there was the Acropolis, rising above downtown Athens, coming up on my side of the cab. I tugged her hand and nodded toward the sight. She leaned over against me, saw it through my window, and said the name in Farsi.

“We go there?” she asked.

I said, “Sure, anything you want.”

I had the driver drop us off at a tavern a few doors down from the Hotel Harakas where I’d already checked in and where Baizan waited for us. Here, deep inside a dark, narrow room cooled by ceiling fans, we sat at one of the scarred wooden tables, the only customers except for four men playing cards by the front window, and ordered a Coke and a beer from a surly young guy with bushy black eyebrows and a three-day beard who was stuffing grape leaves behind the bar. I remembered our first date again—so far my reunion with her had been framed by flashbacks of our week together in December, every moment seeming to happen in two parallel time zones. As if nothing had changed. But so much had changed.

Azi sat quietly, sipping her Coke, poised, even though her chair wobbled whenever she shifted her weight, and patient, even though I was acting like a seventh grader on his first date, staring at her in dumb amazement, asking dumb questions: “Do you want to move to another table?” “Do you want anything to eat?” “Do you want a glass?” “Do you want ice?”

She said “No, thank you” four times, her eyes, amber liquid, regarding me, tolerant, maybe amused.

“Do your parents know about me or do they think you are here with a girlfriend?” I asked.

“My mother know I have letters from you and you are man, and I tell to her telegram come from sister in Greece, also friend, but I think she know this is no true, I think she know you are here. But my father think I visit girlfriend.”

“What did he say?”

“He is angry but, um, he is guilty?”—I nodded—“and he say o-kay I visit girlfriend if I have papers. He think impossible for to get papers, but I have passport before, and visa and ticket come, so everything o-kay. Thank you for to help.”

I held out my hand, palm up on the table, and she placed hers in it. Her other arm braced her stomach as if she’d been wounded there. “I’m sure you have a lot of questions and want to know how and why, all of a sudden, I arranged all this.” She raised her eyebrows and tilted her head as if it wasn’t that important, but if I wanted to tell her . . . . “Well, I’ve missed you so much, as you know from my letters, and the phone call, and I’ve wanted to see you every day, but Americans aren’t allowed to travel to Iran, and I couldn’t have come here, and, most important, I couldn’t have gotten papers for you, and, well, what I mean is that I couldn’t have done it without help. I know this is going to sound crazy, but I’m here because the government has set it up. You might remember that I have a friend who works for President Carter, and after you called, he asked me to meet with you to see if you might be able to help us come up with ideas to solve the hostage crisis.”

She didn’t move, but her face seemed to tighten as if someone had pressed her forehead right between the eyes. Her glance slid off me sideways and landed on the floor between the tables. Her hand shrank in mine. She breathed hard as if the fans were pushing the air out of the room. She had come to see me, of course she had, but I had come because the government . . . . A romantic reunion had just turned into a political maneuver.

But I said, “I came mainly to see you, and if you don’t want to talk about the hostages, fine, we don’t have to, and we get to spend the weekend together anyway.” This seemed to relax her a little, and she settled her weight against the back of the chair.

“Of course, Jay, you ask question, but I no understand—why the government want for you to talk to me. I know nothing.”

“Actually, there is another person here who wants to ask questions too.”

“Who is here?”

“The man who helped you get your visa and ticket—he’s from the CIA.”

She jerked her hand away and stood up, bumping the table, knocking over the empty Coke bottle, saying, “No! No CIA.”

Afraid I’d blown it already, afraid the card players or bartender would call the police to arrest the CIA spy who was torturing his victim, I tried to do five things at once: I caught the Coke bottle as it rolled, set it on another table, held up my hands, stood, and said, “Wait, it’s not like that.” I stepped around the table and she let me hold her. “Azi, listen.” I lifted her chin up so she’d look at me, and she did, as if begging me to start over and get it right this time. “If you want to go home, I’ll take you back to the airport. Right now. But you don’t have to be afraid of these other men. I’ve met with them and I trust them. I’ll be with you at all times, I promise, and I would never let anyone hurt you—you

know that.” No response. “All they want to do is sit with you in the hotel and ask questions about the current situation in Iran. If they ask something you don’t want to answer, just say so, no problem. They’re only looking for intelligence, for information that might help solve the crisis. That’s all. But tell me if you don’t want to do it. I’ll make them send you home.”

Finally she said, “You trust CIA?”

“Yes, I trust these men.”

“But why they talk to me? I know nothing.”

“You know more than they do, you’re the cousin of the foreign minister, and they’re desperate—all their lines of communication with Iran have been broken. I think they mostly want you to talk about Sadegh and talk to Sadegh.”

“They hurt him?”

“No, no, just the opposite. They think of him as an ally. Sadegh met with my friend secretly in Paris. Nobody knows about it because if it had leaked, Sadegh might have been executed. They tried to work out a deal, but for some reason it fell through. Now the people around Sadegh are suspicious of him, so he can’t risk further direct contacts. Still, our government thinks he’s the only hope we have of getting the hostages released, and we want you to tell him we’ll help any way we can.”

She considered that and nodded. “After talk, what?”

“Then you and I have until Sunday afternoon to do whatever we want.”

She looked down. She still seemed bewildered, and I couldn’t guess what thoughts passed through her mind, but then she looked up and asked, “You stay with me?”

“Every minute.”

“We are safe?”

“Yes, they’ve assured me that we have nothing to worry about.”

Messenger from Mystery

Messenger from Mystery